The Untold Story of Hip Hop Be Bop (Don’t Stop) – How Man Parrish Created a Classic and Lost Everything

The Twelve Inch 152 : Hip Hop, Bebop((Don't Stop) (Man Parrish)

What If the Future Sounded Like This?

Imagine a time before hip-hop had fully formed, before electro had a name, and before DJs in New York’s underground clubs had the perfect beat for breakdancing battles. Now, imagine a track so ahead of its time that it still sounds futuristic four decades later. That track is Hip Hop Be Bop (Don’t Stop) by Man Parrish, and its story is as wild as its sound.

But what if I told you that despite its groundbreaking success, the man behind it never saw a dime? This is the story of how a Bronx-born synth wizard created an electro anthem, got swindled, and still ended up influencing generations of dance music producers.

Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre and I’m really glad you’re here. This is “The Twelve Inch”, my newsletter that tells the history of dance music between 1975 and 1995, one twelve inch at a time.

If you’ve received this newsletter, then you either subscribed or someone forwarded it to you. If you fit into the latter and want to subscribe, please do so. That way you will not miss any of my weekly episodes

Who is Man Parrish?

Born as Manuel Joseph Parrish in 1958, he was raised in the Bronx. At a young age, Manuel was placed for adoption and taken in by a dysfunctional family. His adoptive mother was abusive, leading him to leave home at just 14. Seeking refuge in New York’s underground scene, he spent time at clubs like the Mudd Club, where he crossed paths with influential figures such as Klaus Nomi, with whom he later collaborated on his album.

The name “Man” was simply a shortened version of Manuel. As he navigated New York’s vibrant art and club scenes, the nickname stuck, ultimately becoming his musical identity. It was Andy Warhol—who featured Man Parrish in Interviewmagazine—who solidified the name. “Manny’s to common, let’s call you Man, like Man Ray” Warhol suggested, and the name remained.

How Did He Start His Career?

Man Parrish’s career took off in the underground art and music scenes of New York in the late 1970s. Fascinated by electronic pioneers like Kraftwerk, Giorgio Moroder, and Patrick Cowley, he spent his early years experimenting with synthesizers and drum machines. “I wanted to copy what the Brits were doing,” he recalled.

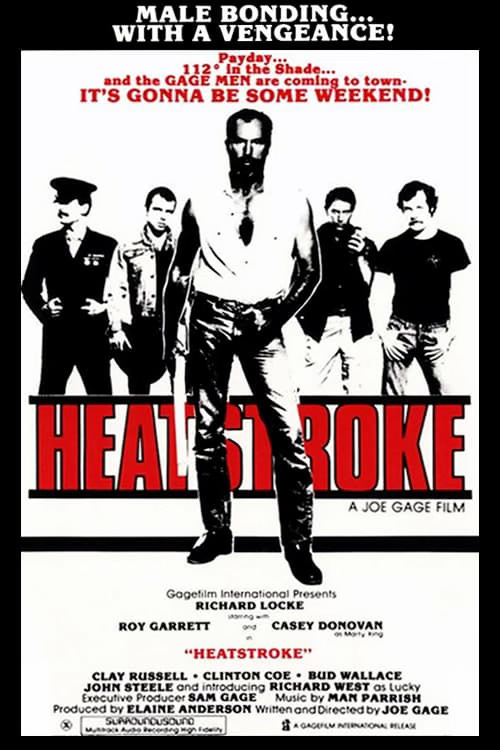

His first break came in an unexpected way—scoring a gay porn film. A friend of his, who wrote for a gay men’s magazine, interviewed director Joe Gage, known for shaping the iconic “gay look” of the ’70s—mustache, tight jeans, aviator sunglasses. During the interview, Gage mentioned he needed someone to score his next film, Heatstroke. Man Parrish’s friend made the introduction, and soon, he was creating multiple tracks for the film, including the title track.

Sadly the “soundtrack” version was never released 😁

About six months later, while at The Anvil, a legendary New York gay bar, Man Parrish heard his track playing. To his surprise, the DJ had ripped the song straight from the Heatstroke Betamax, pressing it onto an acetate—complete with ALL the sounds from the film. 😃

“I said, ‘You’re playing my record! Where did you get that?’ He asked, ‘You did this record?’ I told him, ‘Yes, it’s from Heatstroke, and I’m the guy who made that music.’”

The DJ then mentioned Importe/12”, an indie dance label owned by Mike Wilkinson, who was looking for new releases. Though the label and its management operated on the shadier side of the industry, they were eager for a hit. Man Parrish, a young artist eager to release his music but unfamiliar with industry pitfalls, was the perfect candidate. The label wasn’t run by innovators—it was run by businessmen looking for their next big payday, not necessarily one they planned to share with the artist.

The Swindle

Man Parrish’s new record boss paired him with in-house producer Raul Rodriguez, and together, they sifted through all the music Man Parrish had recorded. “Raul liked everything I played for him, including “Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop),” which, like all of my music at the time, didn’t have a name, just an identifying number (eg: Song Idea #23). Frankly, I hated this song because it had no formal structure like a verse, chorus, and bridge, and I initially considered it more of an experimental track, or at best, an album filler. I was much happier with “Man Made,” because I loved Kraftwerk, and like them, I had a fully synthetic band, and that song had more of a song structure. It was Raul’s idea to develop “Hip Hop, Be Bop” and I just went along with the flow”

They compiled a cassette of possible tracks and presented it to Mike Wilkinson. At their second meeting, Wilkinson was enthusiastic. “Hey buddy! I think you’ve got some great music here! I want to put it out on a new label I’m have, called Importe 12””

Without hesitation, Man Parrish replied, “Sure!” Wilkinson then added, “Before I do that, you just need to sign this slip of paper that gives me permission to use it. Are you cool with that?”

At just 22 years old, Man Parrish made a decision that would change his life. “I don’t know anything about legal stuff, Mike. Don’t I need a lawyer?” he asked.

“No, no. You don’t need a lawyer; it’s just one page and there’s nothing to worry about,”

Trusting Wilkinson’s reassurance, Man Parrish signed away the rights to his most important work—without realizing what he had just given up.

Mike Wilkinson

The Making of Hip Hop Be Bop (Don’t Stop)

After signing the contract, Raul and Man Parrish selected eight songs to refine in a proper studio and got to work. Raul was particularly focused on Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop). They booked time at Vanguard Studios—not the best, but the most affordable option. At the time, Parrish wasn’t trying to make a hip-hop record; he was simply experimenting with rhythms and sequences that felt fresh. This was in the pre-MIDI, pre-computer era, when creating an electronic track was a painstaking process. If you’re curious about how it was done, here’s a video where he explains it all—a fascinating glimpse into the early days of electronic dance music, and I promise, it’s nothing like you’d expect.

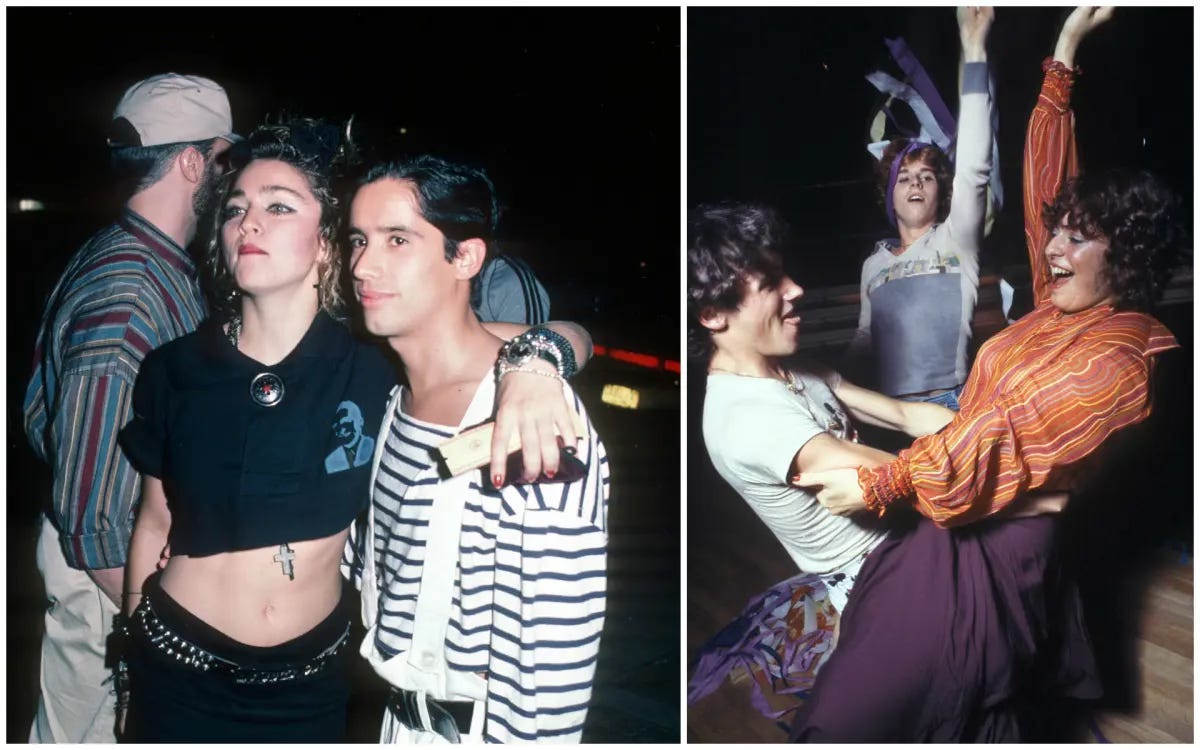

During one of their sessions, Raul invited Man Parrish to The Funhouse, a trendy club known for blending funk with early hip-hop and electro. The first time Parrish stood in the DJ booth, he noticed that Jellybean Benitez—the club’s resident DJ—had a girlfriend with jet-black hair, a cut-off T-shirt, and unshaven armpits. Her shirt read “I Am Madonna.”

“We used to call her a skank because it looked like she hadn’t bathed in weeks,” Parrish recalled.

Madonna, Jellybean and part of the “barking squad”

As Jellybean dropped a record, the crowd erupted. Suddenly, they heard an unexpected sound—a chorus of barking from a few hundred kids on the dance floor. Raul grinned and explained that, at The Funhouse, when the crowd loved a song, they barked at the DJ to show approval.

That’s when inspiration struck.

“What if we took Hip Hop, Be Bop and added dog barks to it?” Parrish thought. “What if we pressed a test copy and gave it to Jellybean? Our track could ‘bark’ at the kids instead of the other way around. If they barked back, it would be this fun, one-off experiment.”

The Secret Behind the Success of the Song

And that’s exactly what happened. When Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) was finished and they handed Jellybean a test pressing, the kids on the dance floor barked—just as they had hoped. That signature bark would become one of the defining elements of the track. It wasn’t just another club record; it was a bold fusion of innovation and the raw energy of the underground scene.

At a time when hip-hop beats were still largely sampled from funk records, Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) was a game-changer—purely electronic, built from scratch. It didn’t just follow trends; it set them. The track’s relentless, futuristic groove resonated with dancers, and B-boys and B-girls quickly adopted it as a breakdancing anthem, its robotic rhythms providing the perfect backdrop for their moves.

One of the excellent remixes

But success didn’t come without resistance. When some Black radio stations and clubs discovered that Man Parrish was both white AND gay, they pulled his music. Despite this backlash, the momentum was unstoppable. Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) (and the album) went on to sell two million copies and climbed to No. 4 on the Billboard dance charts—cementing its place as a pioneering track in electronic music history.

How Did Man Parrish Get Robbed?

Despite its massive success, Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) didn’t make Man Parrish rich. In fact, he got nothing.

How did he end up signing such a bad contract? From what’s been documented, Parrish’s deal wasn’t just bad—it was exploitative. He was promised a 6% royalty, to be paid every six months, but those payments never came. When he went to the label’s office after six months to collect his earnings, he was brushed off with a vague excuse: “We’re a bit behind on the accounting.”

The next time he visited, he noticed the label had moved into a much fancier office. That’s when it hit him—he had been robbed. Realizing the game being played, Parrish refused to record any new music for them, causing panic within the label. He was their only real source of income.

Then, tragedy struck. Mike Wilkinson, the label owner, died of AIDS. In the chaos that followed, two of his employees—who had serious drug problems—forged Man Parrish’s signature and sold the rights to his music to Unidisc in Canada. They pocketed a mere $1,000 for it and blew the entire sum on drugs in a single weekend.

Meanwhile, Man Parrish was scraping by, doing production work and live shows. But the money he earned wasn’t nearly enough to hire a lawyer to challenge the fraudulent sale. The situation was even worse because Unidisc was a Canadian company, meaning he’d need a Canadian lawyer to fight them. To make matters worse, he had no idea just how successful the track was globally—he wasn’t aware of licensing deals with films, TV series, or compilations.

By the time he finally managed to sue Unidisc, the case was dismissed on a technicality.

It’s a heartbreaking story, but sadly, not an uncommon one in the music industry.

Is Hip Hop Be Bop (Don’t Stop) the Song That Coined ‘Hip-Hop’?

Not exactly. The term hip-hop was already in use by pioneers like Grandmaster Flash and The Sugarhill Gang. However, Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) played a crucial role in solidifying electro’s place in hip-hop history—and it was the first track to feature hip-hop in its title.

In the early 1980s, hip-hop was purely dance music, not the rap-focused genre we know today. Rap itself evolved from block parties, where DJs would extend instrumental breaks and MCs began talking or rhyming over them. One of the most famous examples is the extended break in Chic’s Good Times, which directly influenced The Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight.

The title of Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) carries a deeper meaning: “hip hopping” was jazz slang for dancing, while “bebop” was slang for music. So, in essence, the title translates to Dance to the music—Don’t Stop.

What Happened Next?

After Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) and the fallout from his disastrous record deal, Man Parrish struggled to build on his success. He managed another minor hit with Boogie Down Bronx, but his career took another blow when Elektra/Warner signed him—only to shelve his album, effectively stalling his momentum.

In the decades that followed, he remained active behind the scenes, being the tour manager of the Village People, producing music and teaching electronic production. Though he contributed to Male Stripper by Man 2 Man, which became a hit, mainstream success would ultimately elude him.

Conclusion: A Legacy Bigger Than the Charts

Man Parrish may not have made millions from Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop), but he undeniably changed music forever. His track served as a bridge between hip-hop and electronic music, influencing generations of producers and DJs. From Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys to Autechre and Andrea Parker, his music provided the foundation for countless artists—and remains an undisputed classic of early hip-hop and electro to this day.

Now, I want to hear from you! What are your memories of Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop)? Drop your thoughts in the comments.

And if you want to dive deeper into Man Parrish’s extraordinary life, check out his YouTube page or grab a copy of his recently released book. His journey is packed with wild stories—from rummaging through David Bowie’s underwear drawer to encounters with Elton John and Freddie Mercury in the NYC nightlife. Oh, and let’s not forget the time News of the World headlined him as Madonna’s boyfriend. It’s one of the most entertaining reads I had in a long time!

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

Man Parrish in his “studio” in 1984 (when he was recording the shelved Warner album)

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

Alright, B-Boys & B-Girls 😁, time to step up—you’re in for a treat!

This week, we’re diving deep into the early ‘80s Hip-Hop, Breakdance, and Electro scene. If you’ve got the moves, now’s your time to shine. If not, you’ve got a full hour to practice!

We kick things off with a classic—the track that pulled me into early electro (but, unfortunately, not into breakdancing 😃): Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don’t Stop) by Man Parrish. That’s followed by High Noon, one of his productions for Two Sisters. And there’s more Man Parrish magic coming your way, alongside a few gems from Arthur Baker—another key figure in this era.

Midway through, expect some crossover anthems like Harold Faltermeyer’s Axel F, Herbie Hancock’s Rock It, and Malcolm McLaren’s Buffalo Gals. The second half shifts focus to the early rap scene before we wrap things up with Freeez and Dan Hartman.

Get ready—it’s gonna be a ride!

Enjoy !

Next week, I’ll be introducing you to one of the finest examples of French disco that was American produced and clearly aimed for an international market.

Fascinating story. I feel for Man as well as for those artists who are so desperate to cut a break that they end up signing exploitative contracts. However, as you rightly point out, his musical legacy remains unchallenged. Happy weekend!

A gripping read. After punk, there was an assumption that indie labels put the music first but of course there have always been operators like Importe/12" where this is by no means the case. Male Stripper was Top 5 in the UK but I think I first became aware of Man Parrish when I bought the Two Sisters album released on Morgan Khan's Streetwave label. Glad that Manuel is still going strong in his mid 60s to tell his stories, even when all it takes is a bit of Madonna's armpit hair to provoke the usual misogynistic responses!