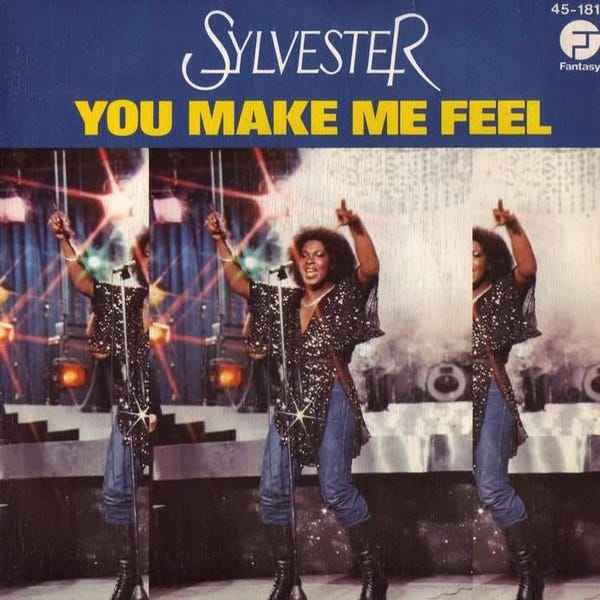

🎤 Sylvester and How ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’ Birthed the San Francisco Sound and Redefined Dancefloor Freedom

The Twelve Inch 164 : You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (Sylvester)

When Sylvester belted out “You make me feel… mighty real!” in 1978, he wasn’t just performing, he was preaching. That track didn’t just light up dancefloors; it rewired them. This wasn’t merely disco. It was liberation, pulsing at 132 beats per minute. But at the time, it wasn’t liberation for me, at least, not yet. My own coming out was still years awa…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Twelve Inch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.