Orgasmic Strings and Eurodisco Beats: How Love in C Minor and Cerrone Rewired the Dancefloor

The Twelve Inch 172 : Love In C Minor (Cerrone)

In 1977, I was 14 and my taste in music was starting to shift. I was no longer just hearing music in the background, I had started listening, really listening, especially to the radio.

We lived close to the Dutch border, which turned out to be a blessing. Belgian radio just wasn’t cutting it (as I explained back in Episode 132 on “Love Epidemic” by The Trammps). But Dutch radio, now that was something else. Disco was on the rise, and my favorite show was the Soul Show on Thursday nights. It was packed with American imports, mostly by Black artists, and full of US-made disco. Eurodisco, a term I’ll come back to in a moment, barely made it onto the playlist.

There were some exceptions, of course. Donna Summer being the obvious one. And occasionally, a bit of Eurodisco would sneak into daytime programming, as long as it wasn’t too risqué. Which brings us to this week’s song: “Love In C Minor” by Cerrone. I don’t think I ever heard it on the radio. 😄

No, the first time I heard that record was during a sleepover at my cousin’s place. He was five years older and had a record collection I was in awe of. He put the album on, showed me the cover… and then came that track. Moaning. Laughter. Bedsprings. A slow, theatrical build-up of breathy pillow talk. Then, the four-on-the-floor kicks in, the strings swell and suddenly you’re swept away into a 16-minute disco odyssey that sounds like Barry White wandered onto a French movie set.

I’m pretty sure I wasn’t the only teenager who discovered Cerrone that way.

And yet, as outrageous as it seemed, it was also an instant classic. Alongside Giorgio Moroder, Marc Cerrone helped bring what would later be known as the “French” and “German” sound, or simply Eurodisco, to the American dancefloor.

So who was Marc Cerrone? Why was he the first (but far from the last) French producer to break through in the US? What exactly was Eurodisco, and how did it become the dominant strain of disco after 1977?

And what’s the deal with that album cover?

If you’re ready… let’s undress and dive in. 🫣

Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre and I’m really glad you’re here. This is “The Twelve Inch”, my newsletter that tells the history of dance music between 1975 and 1995, one twelve inch at a time.

If you’ve received this newsletter, then you either subscribed or someone forwarded it to you. If you fit into the latter and want to subscribe, please do so. That way you will not miss any of my weekly episodes.

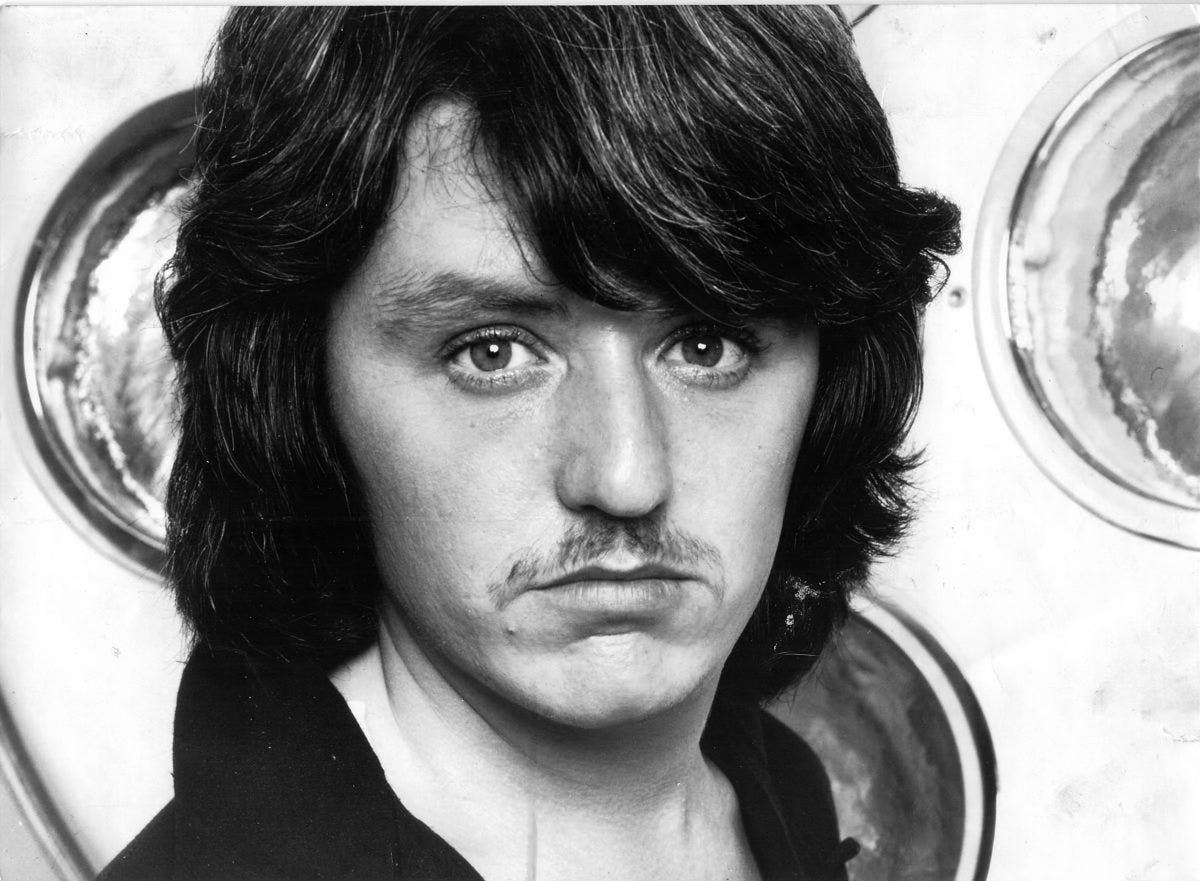

🥁 The Drummer Boy of Paris: Who Is Cerrone?

Marc Cerrone was born in 1952 in Vitry-sur-Seine, a working-class suburb of Paris, to French parents of (partly) Italian descent. After his parents divorced when he was still young, he was placed in a religious orphanage, an experience that only made him more rebellious. Add to that an endless supply of energy, and you had a child who was hard to contain. “Since I was unruly, and not really a good student, I would drum on the tables non-stop and get thrown out of class,” he explained in his biography. His mother offered him his first drum kit if he could last a year without being thrown out of class.

He kept his promise, she kept hers and at 12 he got his first kit. Marc Cerrone started out playing in local bands, but his parents weren’t keen on the idea of a music career. They pushed him to stay in school, and eventually, he did graduate. His father urged him to find a “real” job, but Marc was determined to pursue music. The conflict came to a head, and he left home, spending a period living on the streets. It was the summer of 1969.

At the time, his girlfriend was working as a G.O. (gentil organisateur) at Club Med, one of the staff responsible for creating the social atmosphere in the resort. At the start of the season, Club Med held a gathering for all its G.O.’s. There, Cerrone struck up a conversation with the company’s director, asking why there wasn’t a live band in every club. He pitched an ambitious plan: a rotating crew of drummers, bassists, and guitarists who could tour all the Club Med resorts. It was bold, clever, and it worked. At just 17, he was hired on the spot to set the whole thing up.

The Kongas with Eddy Barclay, spot Cerrone in the lineup?

Through Club Med, he made his way to Saint-Tropez. In 1972, he formed Kongas, a band made up of the most talented musicians from the Club Med network. Their sound was a blend of rock, African rhythms, and soul, drawing inspiration from Santana, Osibisa, War, and Manu Dibango. It was raw, percussive, and rhythmic, steeped in African grooves. Cerrone was influenced by the large West African community in Paris, a legacy of France’s colonial past.

One of the first singles of the Kongas

Kongas eventually got a booking at the legendary Papagayo club in Saint-Tropez. That’s where they caught the attention of Eddie Barclay, a major figure in the French music industry. Barclay signed the band to his label, and they released their first album. They enjoyed some success but the story wouldn’t last. “In the end, like all groups, when you're playing 250 sets a year, you get tired. And I left. I'd had enough. I wanted to quit music.” Cerrone said. He wanted to try something different in the music industry.

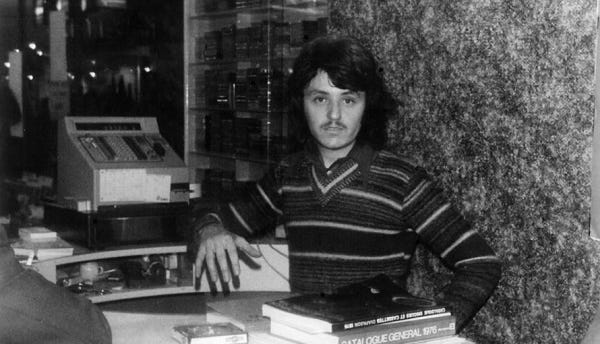

So he opened his own record store, Import Music, focused on bringing in US imports. At the time, France had very few specialist shops, most records were sold from rotating stands in stores that mainly sold something else. Cerrone’s idea took off immediately, thanks to a clever launch offer: customers got a credit of 2,000 francs (around 300 euros) to buy records, with six months to pay it back and zero interest. The trick? He’d negotiated a bank loan at just 4%, a far lower cost than the 10% discount most other record shops gave. It made sales skyrocket. Within a short time, Cerrone had opened nine more stores.

📀 From Record Store To the studio: Where Did the Inspiration Come From?

That question’s easy to answer. Thanks to his record shops, Cerrone had a front-row seat to what moved on the dancefloor, and what didn’t. Because he imported directly from the US, he was always up to date with what was playing in New York clubs. He loved the lush grooves of the Philly sound and Barry White, but he was also drawn to Kraftwerk and their early underground hit Autobahn.

He watched closely as European productions like Silver Convention’s Fly, Robin, Fly, and especially Giorgio Moroder and Donna Summer’s Love To Love You Baby, broke through on American dancefloors. “I said to myself, heck, I'm gonna make one. It's for my last, and I won't compromise on anything”

🎻 From Studio Castoff to Studio Magic: Who Helped Make the Record?

He decided to contact an old collaborator on the Kongas project : Alec R.Costandinos. “One day, he came me, and he said, look. I wanna make an album. My first reaction was, like what? Then I thought to myself, it would have to be a drummer's album”. said Alec R.Costandinos

Cerrone wanted to record in London, and for a pretty ironic reason. He chose Trident Studios over any studio in Paris because he was looking for musicians who could play with that authentic American feel (on a record that would end up defining the Euro sound on US dancefloors 😁).

He knew exactly what he was after: “Alec co produced the album with me. I told him I really like strings, you know, like Barry White. I made him listen to Barry White. I said, something like that'll do. He said, I've got just the guy. I'll introduce you to him. He's worked with Johnny Holiday. He does this. And I said, I don't want French stuff. He said, let me introduce you to him. We'll see what he's got for you”. That’s when he introduced Cerrone to Raymond Donnez, better known as Don Ray, who would go on to become a key figure in French disco.

One of the things people never forgot about Love in C Minor was the female moaning, the playful banter woven into the track. As the story goes, it wasn’t planned at all. It happened spontaneously, right at the end of the mixing session: “I called together everyone who wanted to come to hear the final mix and listen to what I was doing. It was midnight. We pressed the play button. I saw Madeleine Bailey and Sue Glover, the singers, who were stars in their field began moaning at certain points. They said, the way you're making us feel is great. So I asked them, can we not start from the beginning? You know, don't overdo it. Just be natural. Express how you feel. And we record it. So they laughed. They said, sure. Why not? Don't overdo it, I said. We did it, and it stayed on the record”.

Trident Studios London

I suspect there was a bit more intentional planning than Cerrone later let on. He was an entrepreneur who knew exactly what he was doing. He understood that a big part of Donna Summer’s success was the sexual element, and that Love to Love You Baby owed a lot to Serge Gainsbourg’s Je t’aime… moi non plus. So I think the decision to include that erotic touch was deliberate from the beginning. The male voice in the song is Cerrone himself, turning the track into a kind of sexual fantasy.

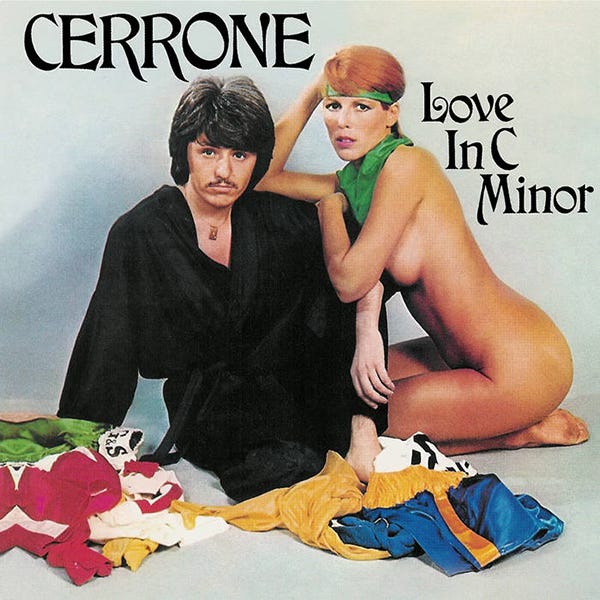

💋 That Infamous Cover

If the moans didn’t raise eyebrows, the album cover certainly did. It wasn’t exactly subtle, and that was the whole point. As most records were sold in general stores alongside all kinds of other products, Cerrone knew he needed something that would grab attention immediately. 😁

They were still fully dressed when the session began 😃

And like the intro to the title track, it walked the line between provocation and parody. In many ways, it was Eurodisco’s first real piece of glam theatre.

📦 DIY Distribution and a US Surprise

Getting the record released was a whole other challenge. French labels wouldn’t touch it. In his biography, Cerrone recalled one of the responses he got: “It’s unlistenable. What is this crazy thing? Do you even know what mixing is? A drum solo pushed to the front, with a kick on every beat. The harmonics and melody buried in the background. And for over fifteen minutes! Do you realize how insane that is?” Cerrone decided to take matters into his own hands. He pressed the record himself and released it on his own label, Malligator, a move that would prove brilliant. When the record took off, he didn’t just earn a standard artist royalty; he owned the rights and reaped the full rewards, well beyond what a major label deal would have offered.

The breakthrough came thanks to a stroke of luck. Around 300 copies of Love in C Minor ended up in New York by accident. A French record store meant to return a Barry White album to the U.S., but mistakenly shipped Cerrone’s record instead. That copy landed in the hands of a key DJ on the record pool, and within weeks, the track was playing everywhere from the Loft to Fire Island.

At first, Cerrone had no idea the song was blowing up in New York. He didn’t even know what Billboard magazine was. It wasn’t until he attended the Cannes Midem conference (used to be the most important yearly encounter of the music industry) in early 1977 and started receiving congratulations from industry people that he realised what was happening. By then, Casablanca Records had already rushed out a cover version.

Cerrone immediately flew to the U.S., and with the help of his French distributor (WEA), secured a meeting with Atlantic Records, one of the American labels in the Warner group. They didn’t need much convincing. They signed a distribution deal on the spot.

By early 1977, Love in C Minor had climbed to No. 3 on the Billboard Dance chart. (doing much better than the Casablanca cover) Not bad for a track most French label execs had dismissed as unmarketable soft porn.

The Casablanca cover.

🌍 The Eurodisco Moment: Why It Mattered in 1977

When Love in C Minor exploded in the U.S., it marked a turning point. A shift had already begun in 1975 with the success of Silver Convention’s Fly, Robin, Fly and Donna Summer’s Love to Love You Baby on American dancefloors. These records, though European, were designed to sound “black”, and convincingly so. Tom Moulton even admitted he had no idea Fly, Robin, Fly was European or sung by three white singers.

But by 1976–77, the European sound had evolved into something else entirely. While American disco was rooted in soul, blues, and jazz, Eurodisco leaned heavily toward pop. The four-on-the-floor beat took center stage, with greater emphasis on melody and lush orchestration. Orchestration, of course, wasn’t unique to Eurodisco, the Philadelphia sound is a prime example of its use in American disco, but the intentions were different. Producers like Gamble and Huff (with Thom Bell) were making soul records that happened to work on the dancefloor. Eurodisco, on the other hand, was made for the dancefloor.

As Giorgio Moroder later explained, part of the simplicity in Eurodisco’s rhythmic structure was deliberate. He didn’t want to make the beats too complex, he needed something the European crowd could easily dance to.

At the 1978 Billboard Disco Awards, Cerrone took home no fewer than four trophies — including Best Artist, which was presented to him by Donna Summer.

So why did Eurodisco suddenly rise to dominance around 1977?

There are three key reasons:

A shift within Black American audiences

While disco emerged from Black and queer communities in the U.S., many in the Afro American community began to see disco as a watered-down version of real soul music. As a result, many artists and producers focused more on soul than on disco itself, leaving the door open for Eurodisco.

Casablanca Records’ marketing machine

Casablanca became a powerhouse in the second half of the ’70s, because they were quick to embrace Eurodisco. Their ability to market and distribute records like Love to Love You Baby was crucial to the genre’s breakthrough. The rise of Casablanca and the rise of Eurodisco went hand in hand.

Adoption by LGBTQ+ club culture

The LGBTQ+ community fully embraced Eurodisco. As one of the most important engines behind the disco explosion, their support helped cement the genre’s dominance in clubs from coast to coast.

By 1977, Eurodisco wasn’t just a curiosity from across the Atlantic, it had become the sound of the dancefloor.

📈 What Came After?

After the success of Love in C Minor, Cerrone released a run of influential albums:

Cerrone’s Paradise (1977)

Supernature (1977), a sci-fi disco concept album with proto-electronic textures and lyrics by Lene Lovich

Cerrone IV (1978), which leaned into electro-funk

Though he never replicated the U.S. chart success of Love in C Minor, his influence continued to grow across Europe. By the early ’80s, his sound had become a key reference point for both Hi-NRG and early house music.

His impact extended well beyond that era. Daft Punk sampled him. Bob Sinclar collaborated with him. And James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem cited Cerrone as an influence on his rhythmic arrangements.

🔁 So What’s the Legacy of Love in C Minor?

Alongside Giorgio Moroder, and to some extent Frank Farian, Cerrone played a key role in breaking Eurodisco into the all-important U.S. market. In doing so, he opened the door for countless other European artists and producers to claim their share of the disco boom.

Cerrone built his sound on what came before. He wasn’t the most skilled drummer or a technically brilliant producer, but he had a sharp instinct for what was happening musically and culturally. He was willing to take risks, had relentless energy, and worked at a furious pace, releasing two albums a year in the early stages of his career, not counting side projects. Add a bit of luck to that, and he ended up living out a career far beyond his early ambitions.

The immediate follow-up to Love in C Minor, released just a few months later.

At heart, Cerrone is a savvy entrepreneur. His story reads like an American dream, just played out in Europe. So it’s no surprise he was one of the first European disco artists to succeed in the U.S. Even without speaking English, he understood the language of the music industry.

Still, business acumen only gets you so far. Cerrone’s disco output holds up because of its sheer quality. The production values were top-tier, and his best tracks belong to that rare group of disco songs that truly deserve the label evergreen.

💬 What About You?

Were you on the dancefloor when “Love in C Minor” first dropped? Do you own the album? Did the moaning intro make you blush… or laugh?

Tell us your memories. And don’t forget to listen to this week’s Mixcloud mix which kicks off with Cerrone’s disco milestone complete with the long spoken intro.

If you enjoyed this story, help me by sharing it so more people can join our community.

Let’s keep dancing. Even if it’s in C Minor.

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

This week’s mix opens with Cerrone’s “Love In C Minor,” complete with its full 1-minute-30 spoken intro. Originally released in 1976, Cerrone’s debut really took off the following year, and it perfectly captures the atmosphere of the US dancefloors in 1977. You’ll hear the growing influence of European sounds throughout the set.

Alongside classic US disco from Salsoul Orchestra, Gloria Gaynor and T-Connection, I’ve also included some deep cuts from the Eurodisco scene: “Body & Soul” from Don Ray’s album, Ornella Vanoni’s sultry “To Voglio,” and Demis Roussos’ surprising disco track “L.O.V.E. Got A Hold On Me,” a favorite at The Loft.

Enjoy

This might sound like the setup for a bad joke, but here goes: what happens when you put together an American, a Russian, and a Korean? The answer? Pure dancefloor gold.

I’ll tell you all about it in next week’s episode, but if you think you already know who I’m talking about, drop your guess in the comments! 😁

This is a fascinating in-depth write-up, should be in a magazine really. I learned a lot here, and I say that as someone who thought he knew a little about (NY) disco. Thanks!

Interesting to read about Cerrone's chain of record supermarkets. Towards the end of the seventies here in the UK, the discounting of albums by priority acts in both specialist stores and general outlets became a major component of record marketing. Be interesting to know if the situation was similar in other European countries. Although Trident was a state of the art studio, when it came to the recording of electronic disco in the immediate post-Moroder era, UK studios weren't considered to be up to scratch, particularly when it came to the toughness of the rhythm sound. I remember this causing great frustration amongst the Human League in their early days.